Get to know UTSC Lecturer Kenneth Boyd, specialist in epistemology, pragmatism, and ethics. “What I want to bring to my class is a healthy skepticism.”

How did you get interested in philosophy?

I think I’ve always been interested in philosophy, at least in some sense, although I didn’t really know what philosophy was until I got to university.

Like a lot of people who have eventually chosen to dedicate their lives to philosophy, I didn’t start out in my academic career thinking that I would be a philosopher. Instead, I went through a couple of different majors first (computer science, and then psychology). Although I found a lot of my classes interesting, what made me decide to study philosophy was the realization that out of everything I was studying, the questions that grabbed me the most were the ones that looked at the bigger picture, that challenged traditions of thought, and went beyond the mere presentation of information; in short, the questions I was interested in were the philosophical ones.

What are you working on right now?

My main research areas are in epistemology and early analytic philosophy.

I have a number of projects in epistemology going on right now. The first looks at what kinds of epistemic obligations we have, both to ourselves and others. These obligations include forming reasonable beliefs, paying attention to information that surrounds us, and gathering the right kind of evidence. My general view is that the epistemic obligations that we have are important and fundamental: just as, say, our moral obligations reflect something important about the kinds of things that we are, so, too, do our epistemic obligations.

Another project in epistemology that I’ve become really interested in looks at what ways knowledge is valuable. While it seems like a platitude to say that knowledge is worth having, it’s not clear whether this is true in general (think about knowledge of the latest celebrity gossip, or the number of blades of grass on someone’s lawn, etc.). Some philosophers have recently posited that knowledge really isn’t that important after all, and that we should focus our attention on something that is really worthwhile, namely understanding. This is my third major project I’m working on: trying to figure out what, exactly, it means to say that you understand something, and whether and in what ways understanding is better than knowledge.

My major research project in early analytic philosophy concerns the work of Charles Sanders Peirce, a 19th/20th century pragmatist. Right now I am working on a project which attempts to reconstruct a pragmatist view of speech acts, with Peirce at the centre.

Who is your favorite ‘historical’ philosopher?

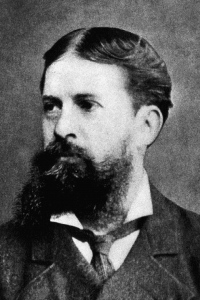

Charles Sanders Peirce

I have a few! First, there’s Peirce. He has had a huge impact on the way that philosophy was done in the 20th century and continues to be done today, but is rarely recognized as such. His writing is also just so much fun to read: you can often find him slinging mud with his contemporaries and, for some reason, obsessing over the number 3. I’m also a big fan of Bertrand Russell, as well as the British Empiricists – Locke, Berkeley, and Hume.

Of the philosophy teachers you found especially influential, what was something distinctive you learned from one of them?

I’ve been fortunate enough to have been taught by some great Canadian philosophers during my degrees, most recently by my PhD supervisor Jennifer Nagel, who happens to be a member of the St. George philosophy department. The philosopher who perhaps solidified my early love of philosophy is Adam Morton, who not only gave me my first proper introduction to epistemology, but also taught me to never be afraid to start down a philosophical path with the full knowledge that it might lead absolutely nowhere.

What do you try to bring to undergraduates in the classroom?

I usually start off the first day of class with a passage from Peirce (of course), who tells us that “in order to learn you must desire to learn, and in so desiring not be satisfied with what you already incline to think.”

Peirce thought that in order to do any kind of inquiry well – be it philosophical, scientific, or even just the figuring-stuff-out that comes along with living your life every day – you should be open-minded, you should never dismiss information just because you don’t like it or where it came from, and never be content to take the beliefs that you have for granted. I think this is exactly right. What I want to bring to my class, then, is a healthy skepticism: I’m not saying that you have to give up everything you believe is true, but I want you to recognize that your beliefs are only worth holding onto if they survive scrutiny.

SHARE